Overview

In part one, we showed that instances classes are hashable, so they can be included as elements of a set object. If the class instance happens to have a set-valued attribute, we effectively have a set with another set as a member, made possible by the instance acting as a “container” (Bernstein, M). In the post that follows, we’ll craft a new class that incorporates the container behavior illustrated in part one, as well as a number of other methods that will prove necessary when we build power sets in part three.

Define a set container class

Using the illustrative example in part one, we will define a new class, ModSet(), with the same constructor and representation methods. New instances of the class will require a set argument, either occupied or empty. In addition, we will define methods to copy, nest and unnest instances of the class.

class ModSet():

# Instance constructor

def __init__(self, setElement):

self.val = setElement # set arg saved in .val attribute

# String eval representation of self instance

def __repr__(self):

return self.val.__repr__() # Return string eval represent.

# of string object in .val

# Method to make a copy of self instance

def __copy__(self):

return ModSet(self.val)

# Modify .val to contain the set of itself, of itself, ...

# nesting .val "depth" number of levels.

def pushDown(self, depth):

while depth > 0:

self.val = set([ModSet(self.val)])

depth -= 1

# Remove one nesting level from set in self.val.

# If un-nested, ignore.

def pullUpOneLevel(self):

listSet = list(self.val)

if len(listSet) == 1:

self.val = listSet[0].val

else:

pass

# Remove height number of nesting levels from set in

# self.val by repeatedly calling above method

def pullUp(self, height):

while height > 0:

self.pullUpOneLevel()

height -= 1

Testing these, let’s define a set of mixed immutables and nest it three levels deep.

worldlyPrez = ModSet(set([('televised', 'summit'), 'DMZ', 12.6, 2019, '\"bromance\"']))

worldlyPrez.pushDown(3)

worldlyPrez

Raising that result back up three levels should return the set to how it was originally defined.

worldlyPrez.pullUp(3)

worldlyPrez

If you instruct to pull up greater than the set is deep, the extra ascents are ignored.

worldlyPrez.pullUp(2)

worldlyPrez

Enforcing uniqueness

Just like Python’s set class, we will make sure that each member of ModSet be unique according to the value of its .val attribute. When a ModSet is comprised of immutables, the set() class enforces uniqueness for us automatically. However, if a ModSet contains other ModSets, we require an additional method to enforce uniqueness among them as well.

class ModSet():

.

.

.

def removeDuplicates(self):

uniqueSet = set() # initialize as empty the unique set to be built

for s in self.val: # s is a member of the ModSet().val set

inUniqueSet = False # initialize match detection flag as false

sTest = s # default conditional testing value for s

for us in uniqueSet: # us is a member of the uniqueSet set

usTest = us # default conditional testing value for us

if isinstance(us, ModSet): # if member us is a ModSet

usTest = us.val # change testing value to its attribute

if isinstance(s, ModSet): # if member s is a ModSet

sTest = s.val # change testing value to its attribute

if usTest == sTest: # compare us and s testing values on this run

inUniqueSet = True # if match, set existence flag to true

if not inUniqueSet: # only add member s to uniqueSet if

uniqueSet.add(s) # match is NOT detected

self.val = uniqueSet # set .val to the uniqueSet from above

Testing the uniqness enforcement method

After we added removeDuplicates() to our class definition, we can test it as follows.

prez1 = ModSet(set([('televised', 'summit'), 'DMZ', 12.6, 2019, '\"bromance\"'])) # inst. 1

prez2 = ModSet(set([('televised', 'summit'), 'DMZ', 12.6, 2019, '\"bromance\"'])) # inst. 2

prez3 = ModSet(set([('televised', 'summit'), 'DMZ', 12.6, 2019, '\"bromance\"'])) # inst. 3

print(set([id(prez1), id(prez2), id(prez3)])) # each instance held in its own memory block

modSetOfPrez = ModSet(set([prez1, prez2, prez3])) # define a ModSet of ModSet instances

print(modSetOfPrez.val) # set class sees each instance as unique though they contain

# equivalent values in their attributes

Now let’s call our uniqueness filter. Only one member should remain.

modSetOfPrez.removeDuplicates() # enforce uniqueness according to attribute value

print(modSetOfPrez) # result after applying removeDuplicates()

Set operator methods

For the power set routines to come, we need instances of ModSet() to join by union and also separate by set-subtraction. Below, we define methods for these operations as well as set-intersection.

class ModSet():

.

.

.

# union-join multiple items, enforce that ModSet members be unique

def union(self, *modSets):

for modSet in modSets:

self.val = self.val.union(modSet.val) # this is union method from set class

self.removeDuplicates() # removes duplicate-valued instances of ModSet members

# take set intersection of multiple items

def intersection(self, *modSets):

for modSet in modSets:

self.val = self.val.intersection(modSet.val) # method from set class

# take set difference of multiple items. Note: arg order matters here!

def difference(self, *modSets):

for modSet in modSets:

self.val = self.val.difference(modSet.val) # method from set class

# version of above method that returns a new instance for assignment.

# Note: only two arguments here.

def diffFunc(modSet1, modSet2):

return ModSet(set.difference(modSet1.val, modSet2.val))

Testing ModSet union

With the set operation methods now included in the class, let’s test union-joining of non-ModSet objects.

charges = ModSet(set())

charge1 = ModSet(set(['obstruction', 'of', 'Congress']))

charge2 = ModSet(set(['abuse', 'of', 'power']))

charge3 = ModSet(set(['incitement', 'of', 'insurrection']))

charges.union(charge1, charge2, charge3)

print(charges)

The three separate ModSets have been merged into a single ModSet, charges. Notice that string member 'of' appears only once, as it should, though it is present in charge1, charge2, and charge3. Now, we’ll test union operation with ModSet members present as well.

First, we’ll nest down by one level each of the three charges, so that we can test ModSet.union(). This time we’re interested in the case when ModSet-of-ModSets are present in the pool of objects to be joined. By “ModSet-of-ModSet”, we mean a ModSet instance that has another ModSet instance as a member of its set-valued .val attribute–the result of ModSet.pushDown(1). During the union call, these ModSet-of-ModSet objects will be routed through paths of .removeDuplicates() that we’ve set up specifically for them.

charge1.pushDown(1)

charge2.pushDown(1)

charge3.pushDown(1)

charges.union(charge1, charge1, charge2, charge3, ModSet(set(['all', 'fake', 'news'])))

print(charges)

You should notice that though we have included charge1 twice in the method-call, its value, {'Congress', 'obstruction', 'of'}, appears just once in the output. So, we may conclude that the .removeDuplicates() method does correctly enforce uniqueness among ModSet-of-ModSet members. Members of {'all', 'fake', 'news'} have been included as well. Now that we’ve shown that .union() works as expected, we can move on to test .intersection().

Testing ModSet intersection

claim1 = ModSet(set(['rounding', 'the', 'bend'])) # define a new instance of ModSet

claim2 = ModSet(set(['dems', 'stole', 'the', 'election'])) # define another new instance

claim1.union(charge1, charge2) # union-join charges 1 and 2 from above with claim1

claim2.union(charge2, charge3) # union-join charges 2 and 3 from above with claim2

claim1.intersection(claim2) # perform set-intersection of claims 1 and 2

claim1 # output the post-intersection result

Above we form two “mixed” ModSet() instances that contain both top-level strings as well as sub-ModSets as members. We can see, after joining the two by set intersection, the result is what we expect: only 'the' remains from the strings and only charge2 survives among the ModSets.

Testing ModSet set-difference

Above we included two methods for performing set-subtraction within the ModSet() class. The first, called .difference(), is an inline function that modifies the original instance from which it is called. Removing charge2 from charges

charges.difference(charge2)

charges

leaves charges with all but the {'abuse', 'of', 'power'} member in the result. So, check.

The second method, that we’ve named .diffFunc(), is a functional version of set-subtraction that returns the result as a new instance ModSet() leaving its originating instances unchanged. To test .diffFunc(), we’ll now attempt to remove charge1 from charges (since charge2 has already been removed in the previous step).

chargesReduced = ModSet.diffFunc(charges, charge1)

chargesReduced

You can see that the value from charge1, {'obstruction', 'of', 'Congress'}, is absent from chargesReduced, though all others from its parent, charges, are present.

Lastly, let’s examine charges to make sure that this particular instance has not been modified since last step.

charges

And there the charge remains, in all its glory, one could say…

Though our testing of ModSet() above has been far from exhaustive, we hope you are convinced that instances of it will behave as we intend them to. At this point, we can finally move on to our main objective: building power sets. We’ll do this in part three to come.

Sources (part 2)

1. Bernstein, M. Recursive Python Objects, https://bernsteinbear.com/blog. 2019.

Get ModSet()

The above code comprises the core of our ModSet() class. We’ll walk-through the power set generating methods in part three. You can download ModSet()‘s complete definition from github: modset.py

The ModSet() class by nullexit.org is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Power sets in Python: an object-oriented approach (part 1)

Overview

In this three part series, we will demonstrate how to construct the power set using both iterative and recursive algorithms. You may recall, the power set of a set $S$ is the collection of all (unique) subsets of $S$, including the empty set and $S$ itself. Though Python's set class does not accept its own set objects as members, we will define a new object class, ModSet(), that encapsulates member subsets in hashable containers so that they can be included within set instance, the power set.

Here in part one, we'll use a minimal working example to demonstrate our solution to the subset inclusion problem. Next, in part two, we construct the ModSet() object with all the methods necessary to support power set generation by two distinct approaches. Finally, in part three we develop and run binary mask and recursive routines for generating power sets in Python.

Now, a bit about power sets.

Power sets defined and how to build them

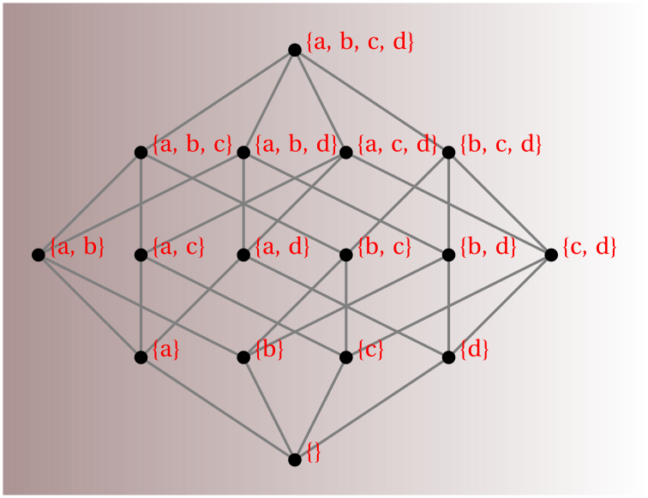

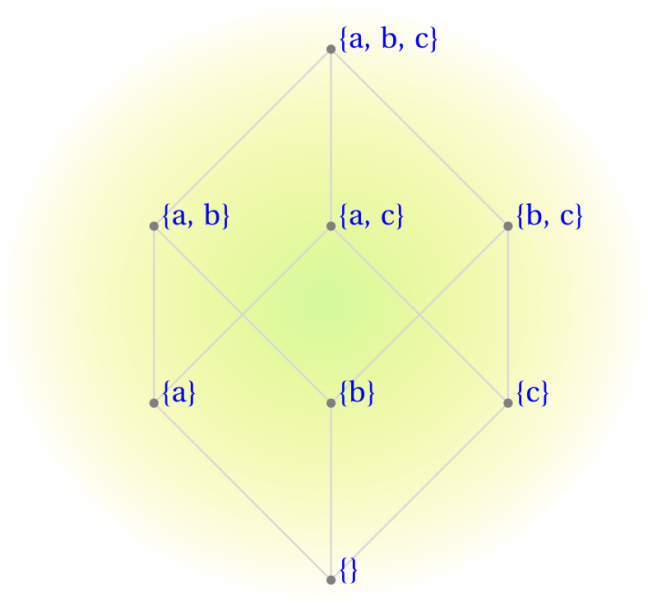

If a set $S$ has $n$ elements, its power set will have $2^n$ member subsets; these include the complete "source" set, $S$ itself, as well as the empty set, $\emptyset$. For example, the power set of set $\{x,y,z\}$ is: $\{\emptyset, \{x\}, \{y\}, \{z\}, \{x, y\}, \{x, z\}, \{y, z\}, \{x, y, z\}\}$. Please notice that there are $2^3=8$ subset elements, all of which are unique; that is, no two subsets contain the same collection of members.

Why $2^n$? Because all possible subsets can be formed by selecting their members according to digit occurrence in the base-2 integers that count from $0$ to $2^n$

Clear as mud, right? Don't worry, we'll explain.

The Binary Mask approach

Say we have a source set comprised of four members, $\{a,b,c,d\}$. The corresponding mask will have four digits that can each take on values of either $0$ or $1$. If a mask digit equals $1$ we keep the element in the corresponding location of the source set, if a digit is $0$, we reject the corresponding element.

Working with binary masks

Here's an illustrative example: binary mask $0101$ operating on source set $\{a,b,c,d\}$ would form subset member $\{b,d\}$ of the power set. Similarly, binary mask $1110$ selects subset $\{a,b,c\}$. Using the same rule, mask $0000$ selects $\emptyset$, while $1111$ forms the original source set of all four elements. There are $2^4=16$ unique bit combinations in a 4-digit binary mask, so there are $16$ unique member subsets in the power set of a four-element source set. Now, extending this procedure to a set comprised of $n$ elements rather than $4$, you can see that its power set will have $2^n$ member subsets by the same rule (the binomal theorem).

The above procedure may seem to have a certain efficiency and elegance in its directness; in this series, we'll call this method "the Binary Mask approach".

But there is another procedure we can use to build power sets...

A Recursive approach

Alternatively, you can take your source set, $\{a,b,c,d\}$, remove one of its members, $a$, then define a new subset with the members that remain, $\{b,c,d\}$, and include it as a new element in a collection. We apply the same element removal procedure to the resultant subset from the previous step, then to the result of the current step, and to the result of the next step, and so on, until we are left with a result that is empty. If we repeat the removal operation for all members of the starting set and each resultant subset, you will produce the a collection of subsets that includes the power set, with many redundant subsets in the collection as well. We'll address this issue of duplication in the next section.

Recursion walk-through

For example: removing $b$ from our source set leaves subset $\{a,c,d\}$. Removing element $c$ from subset $\{a,c,d\}$ leaves subset $\{a,d\}$. Taking $a$ from subset $\{a,d\}$ results in subset $\{d\}$. And finally, removing element $d$ from subset $\{d\}$ produces the $\emptyset$. Then we go all the way back up to the top, this time taking $c$ from $\{a,b,c,d\}$ and repeat the entire stripping procedure until we are left with $\emptyset$ as above. Next we do the same starting with members $d$ and $a$; repeating the full stripping procedure for each.

Notice that we could have removed any existing member from any set or subset at any step in the process--not only the particular members stated above. For example we could have removed $d$ from subset $\{a,c,d\}$ instead of $c$ at that step. If we explore every possible sequence of element removal, we'll notice that identical subsets can be produced by different sequences (e.g. $\{a,c\}$ results from sequence $\{a,b,c,d\} \rightarrow \{a,b,c\} \rightarrow \{a,c\}$, as well as $\{a,b,c,d\} \rightarrow \{a,c,d\} \rightarrow \{a,c\}$). So, our algorithm will need to exclude non-unique subset candidates from the collection; either as the power set is being populated or by removing duplicates after the entire collection has been formed.

Motivation and next step

This second procedure for generating power sets we'll call "our Recursive approach"1. While our Recursive approach may lack the directness and efficiency of the Binary Mask algorithm, we hope that coding it will at least prove to be an instructive, "chops-building", exercise in recursion, if no other utility can be found for it in the future.

Before we can implement either algorithm, however, we need to investigate the behavior of Python's set() class. Specifically, if it suffices for our purpose of containing subsets within an all-encompassing superset, in our case: the power set.

[Spoiler alert... it doesn't.]

The Python set class

The set class in python takes only immutable types (e.g. strings, numeric values, and tuples) as members. Under the hood, a set() object retains a hash or pointer to an immutable object that is a member.

shinyPrez = set([20.1, 2017, ('alternative', 'facts'), '\"record-setting\"'])

shinyPrez.add('covfefe')

shinyPrez

Something to notice: the ordering of elements in the set's output string does not match their ordering in its definition. Unlike Python's iterable list() class, set() objects do not retain member ordering.

When you try to insert a mutable type, lists or dictionaries for example, Python will spit back an 'unhashable' type error.

shinyPrez.add(['Cambridge', 'Analytica'])

See, no dice. Also, because set() objects are mutable, the same goes if you attempt to include a set as a member of another set.

woopsy = set([('impeachment', 'proceedings')])

woopsy

shinyPrez.add(woopsy)

Though you can join sets together, by combining unique members into a single pool, with the set.union() operation.

shinyPrez = shinyPrez.union(woopsy)

shinyPrez

Class instances can be hashed

Now, because separate instances of a class are allocated their own locations in memory, they are hashable; even if they contain unhashable values as attributes. And, even if the values of the attributes of the two instances are equivalent.

class Advisor():

def __init__(self):

self.val = {'Presidential', 'pardon'} # Attribute contains unhashable set

RogerS = Advisor() # has set for attribute .val

PaulM = Advisor() # has same set as above for its attribute .val

modelCitz = set([PaulM, RogerS]) # include the two instances as members of a set

print(type(modelCitz)) # c is indeed a set

print([type(el) for el in modelCitz]) # members of the set are instances of Advisor class

print([type(el.val) for el in modelCitz]) # attributes of member instances are sets

We adopted the above definition from Max Bernstein's blog. Also, we can instruct that instances of the class, when called, define themselves as their .val attribute (Bernstein, 2019).

class Advisor():

def __init__(self):

self.val = {'Presidential', 'pardon'}

def __repr__(self): # method to generate representative code string

return self.val.__repr__() # return __repr__ code string for the

# Advisor().val attribute

MichaelF = Advisor()

noHarmDone = set([MichaelF])

noHarmDone

A quick look might suggest that we bypassed set()'s exclusion of mutables here. But don't be fooled. While we have the appearance of having a set object contained within another set object, what we actually have is a set that contains a hash to an instance of Advisor() that has a set as an attribute.

print(type(noHarmDone)) # Notice that set()'s lack of indexing

print(type(list(noHarmDone)[0])) # methods can be a bit

print(type(list(noHarmDone)[0].val)) # of a pain..!

Why define a new class?

The skeptical Python programmer at this stage is likely asking her/his/them-self: "why don't you just use a list object rather than defining a whole 'nother class for cryin' out loud!?!" Number 1, lists are not hashable; for our power set generation routines to come, we require a container that is. Number 2, lists permit duplicate entries; enforcing member uniqueness would require more coding. Finally, number 3, lists preserve element ordering; while not a deal-breaker for our purposes, lists do not mathematically qualify as sets for this reason and others.

Plan for part two

In part two, we'll define a new class, ModSet(), that will behave much like Python's set() class, but with an added set-valued attribute. Our ModSet() class will employ the same approach just demonstrated above: use of a hashable class instance to contain unhashable set objects. With these container instances themselves eligible for membership in a super-set() object. Use of ModSet objects will allow us to form an all-encompassing power set that--indirectly--has sub-set() instances as members. More than a cosmetic device, defining a set container class in this way will allow the power set of a given set object to be generated using Binary Mask and Recursion-based algorithms later on in part three.

Sources (part 1)

1. Bernstein, M., Recursive Python Objects, https://bernsteinbear.com/blog. 2019.